The Playbook for a Community Charitable Pharmacy

Introduction

So you want to build a charitable pharmacy?

Great news! That is a noble effort, and certainly worth your time. A charitable pharmacy is a world-changing enterprise for your community’s uninsured, low-income population.

Unlike other safety net services located in towns and cities, a charitable pharmacy is the single best way to ensure stable access to consistent supplies of medications for those unable to afford to buy them.

Among other benefits, a community charitable pharmacy will provide a massive new resource serving medication access, will benefit the financial position of your local healthcare industry, and provides a substantial impact on the health and well-being of the community. While a great deal of work and funding will need to go into building a community charitable pharmacy, there is a powerful return.

Further, completing this effort adds you to the ranks of many other leaders in the United States who have also built a charitable pharmacy. Among that community, you will find fellowship, shared vision, and a community that is excited to learn with and from you. We applaud your vision and welcome you to this effort.

A champion is a coach, visionary, manager, and lead encourager to the work of building a safety net enterprise. Building a charitable pharmacy can take anywhere from a few months to several years of work, depending on the readiness of your community and the engagement of the much-needed resources.

You and your leadership collaborative will establish operational aspects that are as varied as hiring the right staff, finding a suitable facility, creating a nonprofit corporation, raising adequate charitable dollars, and managing the supply chain. This playbook attempts to take the learnings of dozens of established community charitable pharmacy programs and the expertise of a large number of veteran leaders, and roll all of that learning into a usable document and toolset.

Our hope is to make your work easier, less risky, and happen faster. So, in the spirit of collaboration, we wish you the very best and hope to help you along the way with the following material.

So what does this playbook hope to empower building?

A community charitable pharmacy is a pharmacy that serves with the expressed purpose of improving health outcomes among the vulnerable by reducing health disparities and increasing medication access.

Typically, a community charitable pharmacy includes standard business features, such as:

- Structured as a nonprofit 501(c)3or equivalent (university nonprofit, government nonprofit, etc.). Community charitable pharmacies can be owned by a nonprofit (like a hospital) or can be a stand-alone nonprofit corporation. This playbook, while useful in any charitable pharmacy design, will be focused on the most complex design – that being a stand-alone 501(c)3 – including legal, fund development, and board development activities unique to the design of such a model.

- In receipt of a valid, current pharmacy and/or pharmacist license, or similar dispensing authority. Each state manages charitable pharmacy licensing in different ways. The principle is that every charitable pharmacy is properly licensed, existing under the authority of all applicable oversight organizations pertinent to their locality.

- Adherence to all local and federal regulation pertaining to the management of a licensed community charitable pharmacy and/or clinic. Again, each state has different regulation governing a charitable pharmacy. This regulatory imperative impacts licensing, staffing, operational design, and other features of a community charitable pharmacy.

- Dispensing a therapeutically broad formulary of medications for free or at a significantly reduced cost to the patient. That means that a charitable pharmacy is primarily focused on increasing access to medications and reducing disparities.

- Bridging patients to external programs (such as Patient Assistance Programs, mail-order discount programs, vouchers, etc.) that are free or which assure a significantly reduced cost to the patient. At times, the role of the community charitable pharmacy is to dispense medication, and in other instances, it is to ensure that the most financially and operationally effective medication access solution is used. While not always the case, community charitable pharmacies generally seek to do this with and through access-expanding programs such as Patient Assistance Programs, donated medication programs, and other such services. Ideally however, community charitable pharmacy programs are organized around programs that have a broad primary care formulary, with medications already stationed in a local inventory(so as not to delay access to the patient) and are dispensed immediately and with as little process and delay as may be possible.

- Eligibility processes which determines qualification for income status (not precluding other eligibilitystatus features specific to the goals of each site, such as: health insurance status, assets, etc.). Typically, community charitable pharmacies are focused on serving those with limited access to healthcare coverage, and limited financial means. This means that enrollment into a qualifying set of patient status guidelines is a part of the community charitable pharmacy’s effort.

- Processes, culture, and systems which assure the dignity and respect for each patient served.

- Business hours and dispensing practices which allow for patients’ continual access to their medications, should the patient seek such access.

- Integration into the community healthcare safety netto support inbound referrals from prescribers for qualifying patients as a standard business practice (private practices, hospitals, free clinics).

- Integration into the community healthcare safety netto support outbound integration with community services necessary for improving health outcomes (medical home enrollment, care management, public health coverage model enrollment, ancillary medical services, etc.)

The above features of Community Charitable pharmacies form a three-part strategy, which has been studied and proven (research described below) to result in a positive impact on health outcomes:

- Carry essential medication via a smart, therapeutically-effective formulary targeted to manage primary care health conditions,

- Dispense the volume of medication needed to serve all patients, and

- Provide that medication in a consistent supply, day after day, year after year, for the patients who maintain health through medication therapies.

Every complex effort needs a champion… the person who stands for the completion of the complex effort and who manages resources and the passion of others to achieve that goal. Perhaps you have championed a large-scale effort before? If so, one of the things you will have experienced is that the attitude and beliefs of the project champion is more critical to the success of the program than any external resource that you will align, including funding or a facility. The outcome of your community effort will be impacted greatly by the attitude and mindset of the leader(s) involved in creating and managing the effort. The good news is that attitude is a choice. The following are a few attitudes that other community charitable pharmacy leaders have noticed that impacted their effort to build a community charitable pharmacy. Take a moment to consider those listed below and if they are currently a strength of you and your coalition, or if further work can be completed to sharpen your attitude in the following areas of attitude competency.

- Administrative Cheerleading – Leadership is difficult work. The primary role for the championis to keep others engaged and moving forward. Certainly, efforts which at minimum require a collaborative leadership team’s work over a series of months require a cheerleader who can be responsible for themselves, and assist others in managing their work. That calls for a deep emotional well, a willingness to not allow delays in progress and excuses to eliminate your passion, and administrative prowess. The happy news – engagement and administrative skill can be learned! If you do not feel like you have every gift needed in engagement management and passion, step out and start the work. The reality is that you will have time to practice, and to strengthen your skill set as you and your collaborative team complete the work.

- Determination – Have you ever helped to open a nonprofit charity before? You will be working in a great deal of ambiguity – completing tasks with a consortium of others, with a definitive-though-vague sense of the destination, and an, at times, foggy vision of the priority of the next steps. This type of leadership is most comfortable for the risk-taker, the entrepreneur, and the visionary. But you do not need to have gotten an MBA in business formation to step out and try. Again… determination is a skill that is learned, as you complete the work.Often times those in the pharmacy industry, particularly pharmacists, like clear answers and guidelines to follow along with. There is not a “quick” answer to when your community charitable pharmacy should be operational, and there is a great deal of ambiguity as to which tasks should be tackled first. This playbook will offer you some idea of a rough timeline and activities involved in the work before you, however, there isn’t really a firm timeline to the work you are leading. Hang in there. Stay determined. Stay positive and keep your collaborative group moving forward. And the more you and your collaborative team face ambiguity, the more your practice and add to your entrepreneurial skillset.Here is an example. Let’s say that your project needs a facility, that facility needs to be donated space, and the perfect donated space is already empty and located in a hospital physician’s The location is vacant, on the bus line, located near the highest heat map zip codes of the uninsured. However, the CEO of the hospital owning that space is known to be difficult to engage for new work among people he does not already know. So, after a great deal of effort and networking, you present your idea to the CEO, and hear a “no”. Anyone looking to start a charitable enterprise will hear “no” many times. Here is the discipline to practice – when you hear “no”, train yourself to think that they are not yet ready to commit to your community charitable pharmacy, and that new ways are needed to get to your “yes”. You have the opportunity to not be a victim, but instead, to make choices, strategize, and keep working to get to your yes. By not being a victim, you enable yourself to listen and determine what deals can be made. Allow the word “no” to free you to design new solutions and create what you need to happen. Entrepreneurs are not always the smartest people in the class… but they know how to stay determined and engaged, even when they hear “no”.

- Lack of Ego/Emotional Maturity – People like to give, but they want to give into places where they will have ownership and be celebrated. To launch your community charitable pharmacy, you will need the help of a long list of others. Those that your project will need might not be as emotionally mature as you need them to be or may have goals that conflict in some ways with your vision. Perhaps a mayor’s office or hospital CEO who might provide donated pharmacy space. Perhaps a church pastor who will bring the congregation to refurbish the space. Perhaps a fund development expert who will bring funding. Perhaps an attorney who will help with your incorporation. The putting aside of your own ego is a discipline you will have the opportunity to cultivate in order to serve the cause ofthe community charitable pharmacy. You may need to manage the expectations of others, their delays, over promises, and changes in priority in order to get to your goal. Again, some good news, emotional maturity and egoless leadership can be practiced and cultivated.

- Networking – Networking is critical in starting up your charitable pharmacy – but not like you may think. Golf games, evening dinner parties, and health system networking events are fine. But to launch a community charitable pharmacy, you may need to seek out people who you do not know and who control resources that you need. Don’t be discouraged if you are not a natural networker or extrovert. Rather, embrace the challenge of reaching out to others for a purpose, getting known, and creating energy in them to see the launch of a community charitable pharmacy.

Championing a community charitable pharmacy takes character and skill. The good news is that the skills you need can each be practiced and learned. They can even be failed at and restarted. Know that the course of your work is going to establish an important healthcare program for your community, and at the same time will establish an important new enterprise in your heart and mind. Give yourself grace, try, fail, try again, and keep envisioning the opening of your community charitable pharmacy.

One of the first steps in your work is to involve a community collaborative, representing the key stakeholders in medication access. While not a complete list, the following leaders, agencies, and businesses are typical suspects in the creation of your community charitable pharmacy. You might consider starting a small group of passionate leaders, at first. But over time, expand your community charitable pharmacy leadership to have engaged the following for assistance, leadership, administrative help, facility space, donations, and staffing:

Health System/Hospital Leadership – Aside from the patients themselves, hospitals have the most to gain in seeing the launch of a community charitable pharmacy. Inpatient care and Emergency Department services to treat otherwise avoidable conditions among the uninsured cost billions of dollars annually for hospitals. This uncompensated care will be greatly impacted by your community charitable pharmacy. Work with your hospital leadership to identify resources and funding. They are often the most willing to help.

Medical Societies – Physicians care about their patients. They get frustrated that patients, particularly the uninsured, may decline in health specifically because the medication needed is unaffordable. Medical Societies offer the administrative organization access to the heart (and wallet) of the physician community. Work early and directly with the medical societies and local physicians. They will champion your work with you.

Boards of Pharmacy – It would be a mistake to assume that the Board of Pharmacy is simply the rule making and rule enforcing structure in a state’s pharmacy access system. Rather, the board of pharmacy is composed of smart pharmacist leaders, who care about the uninsured and care about the transformation of the community to serve better health outcomes. Engage the Board of Pharmacy about design questions, but also ask for their expertise as you build your work. They will help you do it efficiently, and correctly.

Public Health – The local health officer is responsible to improve the health of the community. They and their staff can assist you in finding funding, the best facilities, and other resources to serve your work.

Free Clinics – Unless your community is rather small, there is probably at least one free clinic in the area. If there are more than one, they often meet to discuss issues such as funding, operational design, patient care, and other topics. Be sure to engage with the free clinic community to complement their strategies for community health, to align operational systems, and to work together to achieve overall health improvement.

FQHCs – Not unlike the free clinics, federally subsidized clinics (called Federally Qualified Health Centers) exist in almost every community. Be sure to work with them to align operational design and to complement existing services.

Schools of Pharmacy – A ready source of research support and volunteer students exist at local schools of pharmacy. Be sure to work with the leadership of the schools to maximize your integration with their work.

Faith Community – Often, churches, temples, mosques, and synagogues have operational features that support the healthcare of the poor, and which provide funding for good ideas. Often, the faith community in an area has a collaborative structure or ecumenical council that meet to consider new ideas and resources.

Government Leadership – your local mayor’s office can be a great help in starting a community charitable pharmacy. The staff at the mayor’s office has the networking connections and relationships to identify answers to key questions.

There are a number of partners in a given city or community ready to help you achieve your vision of a community charitable pharmacy. When it is time to educate these and work to launch an operation, start by building relationship and sharing vision. Often partners will want to know you, as well and know your vision. Some other partnership opportunities not listed above include:

- parish nursing programs,

- disease-specific coalitions,

- transplant coalitions,

- for-profit healthcare providers,

- health coalitions,

- engaged community leaders, and

- the chamber of commerce.

Preoperational Steps

- Create the vision and guiding coalition

- Establish a business plan (See Appendices/Business Plan)

- Identify funding – seed and ongoing (See Initial Funding for a Community Charitable Pharmacy)

- Engage with community partners, regulatory, and operational partners

Operational Design Steps

- Identify facility and prepare it

- Identify staffing and train them

- Identify supply chain partners

- Begin marketing

- IT Hardware and Pharmacy Operating System

- Soft Launch

Opening

- Ready the facility

- Stock inventory

- Opening day

Post-opening and ongoing maintenance

- Collect and measure process and outcome metrics

A business plan defines who you are as an organization, what need or issue is being addressed, how you propose to meet that need (goals and objectives), and how success will be measured. Your business plan is a written document that provides a road map for the future of your charitable pharmacy. Keeping it up-to-date ensures that the focus and mission of the pharmacy continue to be relevant and are being met. Sections include finance, marketing, pharmacy management, limitations or constraints and any supporting documents.

A summary of the process of developing a community charitable pharmacy is found in the appendix.

With the implementation of the Affordable Healthcare Act, tax-exempt hospitals became required to implement a Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) every three years. Many of the same assessments are useful in determining where a charitable pharmacy is to be located based on community need. Factors assessed by CHNA include:

- Demographic Assessment identifying the community the pharmacy will serve

- Population by age group, sex, language

- Income, insurance, poverty level\

- Public transportation, housing status, education status

- A community health needs assessment survey of perceived healthcare issues

- Quantitative analysis of actual health care issues

- Health Behaviors and Outcomes

- Appraisal of current efforts to address the healthcare issues

- Access to healthcare providers (hospitals, clinics)

- Locations of hospitals and FQHCs

- Formulate a 3-year plan – the community comes together to address those remaining issues collectively, ultimately working towards growing a healthier community

- Who are potential local collaborators to improve health outcomes through improved medication access?

- What other agencies exist in the community that are providing similar services (free medication, aid with PAP applications, etc.)?

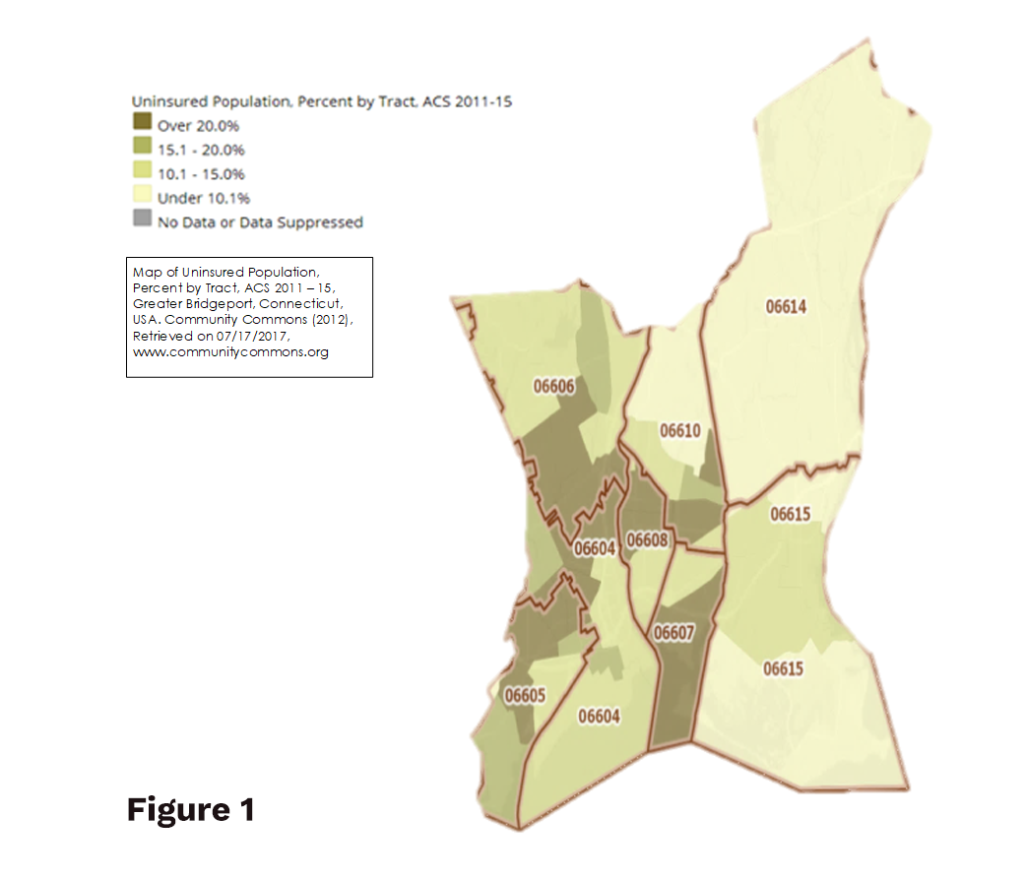

Geo-mapping (Comparing data to a geographical area: ZIP code, city, county, state, etc.) allows visualization and analysis of data as it relates to geographical information (zip code, city, county, state). Comparing a possible site for a community charitable pharmacy to health disparities provides insights for the population being served. Disparities include lack of insurance, chronic disease states, transportation to health providers and/or pharmacies, language, and poverty level. Data comparisons with location can be a convincing visual for potential partners and funders.

Figure 1

Uninsured population, Percent for Bridgeport, Connecticut with ZIP code delineations.

This geo-map can help determine need within the city, where that need is greatest and possible locations that would be nearest the population in need. A comparison to number of patients served and prescriptions filled reflects how well the population’s needs are being met. See How Much Did We Do or How Many? and Appendices/ Marketing/Building a Map of Impact

Some free online sources for this information are the US Census Bureau, Community Commons, City-Data, and City Health Dashboard.

- The United States Census Bureau offers access to specific data from the US census (2010) and the American Community Survey (ACS) which is conducted continually and published annually.

- CommunityCommons.org is a website offering common use of the census bureau data by communities with tools to “improve communities and inspire change.” Data can be linked to maps (state, county, city, zip code) to relate data to a specific location. This is useful when determining the location of the charitable pharmacy (See: Location) and in assessing impact of the pharmacy on the community (See: Results-Based Accountability). Sample stories and maps are available to view and adapt to your situation as well as creating maps to fit a specific need. Training tools are available.

- City-Data.com collects and analyzes data from a variety of government and private sources to create detailed, informative profiles of cities in the United States. Though not healthcare-related, data relating to income, transportation, born outside United States, population density, unemployment, and poverty status are factors affecting a charitable pharmacy population.

- City Health Dashboard is an interactive tool that provides access to health-related statistics –from housing costs to high blood pressure to premature birth rates in 500 cities across the United States. Data can be broken down into a region within a city and allows comparison of statistics to other cities or the national average.

A Pharmacy Desert is a low-income census tract or zip code where a substantial number of residents have low access to a community pharmacy. This definition is based on the USDA definition of a food desert. Patients with chronic diseases living within a pharmacy desert face tough challenges with regards to medication access and information. Several methods can be used to determine a pharmacy desert.

An urban pharmacy desert can be defined as a low-income community or neighborhood with no pharmacy within a half-mile for those with limited vehicle access. For low-income communities with adequate vehicle access, the defining radius extends to a mile.

A rural pharmacy desert is defined as any area within a 10-mile radius without ready access to a community pharmacy (for those that have access to transportation).

Another measure used for determining a pharmacy desert is the density of community pharmacies per 10,000 residents in an area with predominately a low-income (or minority) population compared to areas with moderate income (or non-minority) population (See: Evaluation of racial and socioeconomic disparities in medication pricing and pharmacy access and services).

In determining a pharmacy desert, considerations in an urban setting include resident access to individual or public transportation, walking distance to pharmacy from public transportation, and home prescription delivery service. Limited transportation is also a consideration in a rural setting. A survey to evaluate disparities conducted in Shelby County, TN included “out of pocket” costs of three medications, hours of operation, home medication delivery, a generic drug program, immunizations, and MTM services.

A community charitable pharmacy may be able to address the issues seen in a pharmacy desert by improving affordable medication access and medication information. Locating in or near a place already frequented by the population in need reduces transportation barriers. Mail-order charitable pharmacies offer home or close to home delivery for rural populations (See: Location and Models of Community Charitable Pharmacies).

After considering individual and local factors involved in starting a charitable pharmacy, another assessment is a global look at the environment. PEST Analysis is a simple and widely used tool to help analyze the Political, Economic, Socio-Cultural, and Technological (Legal and Environmental) can also be added) changes in an industry environment. These changes can be opportunities, as in new technologies, new funding streams, changes in government policies. Or they may be threats, as in deregulation that exposes intensified competition, increased interest rates, or a shrinking market. Examples of this type of global influence were the implementation of the Affordable Health Care Act, Medicaid expansion, and e-scribing. The status of 340B may be a factor in coming years.

A sample PEST (LE) Analysis exercise is in Appendices/Business Plan/CSHP_WhatsYourStrategy2018 (See: Environmental Factor Resources for references on concise, current information regarding health, medicine and scientific discovery).

As PEST looks at the “big picture”, SWOT explores these factors at a business, product-line or product level. SWOT Analysis explores Strengths, Weaknesses (often internal), Opportunities, and Threats (internal or external). SWOT can be used to evaluate factors that are sustainable and those requiring closer dialogue. (See: Appendices/Business Plan/CSHP_WhatsYourStrategy2018) for a PEST exercise and example of a SWOT analysis.

Detailed information on PEST (LE) and SWOT can be found at Mindtools.

Phil Baker of Good Shepherd Medication Management offers these points to starting a stand-alone charitable pharmacy.

Good Shepherd Medication Management is a nonprofit organization of Christian pharmacists dedicated to providing pharmacy services to the under-served in Memphis, Tennessee. This nonprofit was created to be Memphis’ first charitable pharmacy, dispensing to low-income uninsured patients for free, specializing in personal patient counseling services.

- Acquire nonprofit status in state where pharmacy will exist (See: 501(c)3Nonprofit Status).

- Develop a three-year budget (See: Example of Initial Budget). Start fund development once at least the first year’s budget is defined.

- Strive for funding from more than one source, a minimum of three. If initial budget is $450,000 for 3 years and $150,000 is needed for the first year, seek “Matching” funds from three different organizations. Example: $50,000 per year from 3 different sources on an annually recurring grant for three years. Funders may be more amenable to a smaller recurring grant than one large single grant. Securing one grant allows time to pursue the other two.

- Partnerships:

- Hospitals – most nonprofit hospitals have foundations that can (sometimes) be sources of funding. Transitional care programs are a great place to partner for direct reimbursement.

- Pharmacy Schools – not sources of funding but essential to a healthy program. Become a preceptor site for local schools as quickly as possible. Precepting fees bring in revenue and students can be utilized throughout the program as they learn various pharmacy processes and develop skills for serving an uninsured population.

- Foundations – Connect with local foundations as early as possible. These are great sources of funding, but they are relationships that take a long time build (See: Fund Developmentand Relationship).

- After securing at least one supporter, the next focus is finding a location. Encourage the new “supporter/s” to help find the best location for free (See: Location).

- Once a facility has been acquired, work with the state for licensing as a pharmacy and/or wholesaler/distributor, related to reclamation. The state may require a wholesaler/distributor license if transferring reclaimed meds from the facility to another facility/pharmacy (See: Registrations and Steps to Obtaining a Pharmacy License).

- Initiate contracts with nonprofit distributors: Dispensary of Hope, AmeriCares, Direct Relief, SIRUM and others. Determine a starting inventory and place an initial order (See: Developing a Formulary and Vendors).

- Technology: (See: Resources)

- Website

- HIPAA Compliant form on website.

- Pharmacy Software

- Billing software

- Customer Relationship Management(CRM) Software

- G-suite for email, contacts, drive space

- Publicity: (See: Marketing and Community Outreach)

- Community

- Host a grand opening event and maximize publicity.

- The first 12 to 18 months are primarily about publicity. Plan on spending at least 50% of time outside the pharmacy speaking to anyone who will listen (primary care providers, other safety net providers, rotary clubs, and anywhere you are invited to speak).

- Recruit (or hire) a local PR professional and plan some sort of press release or event every 30 days. Every new partnership (school, foundation, hospital, etc.) is an opportunity for a press release. Publicity builds credibility as quickly as possible. Under a web search for the pharmacy, the more articles that come up, the more credible the pharmacy is seen.

- Patients

- Recruit patients through partnerships with hospitals, other safety-net providers and speaking engagements.

- Enroll patients

- in person (walk-ins)

- over the phone

- through pharmacy website

Get access to the full playbook

Get instant access to the full playbook, with more than 150 pages of valuable guidance, case studies and resources to help you develop your charitable pharmacy.