Fund development is a process of letting the best ideas compete for limited resources. Before we talk about funding, let’s talk about how we lead. We are leaders. That means that in our work, we must always discern and call others to discern the deepest principles driving the work. In fund development, the principle that should guide us is that the resources at our disposal should always be invested in a way that best serves the patient.

Resources are limited. In small, financially limited free clinics, even to the financially comfortable health system, every dollar is and should be scrutinized. Said in one way, the “idea” of a community charitable pharmacy should be compared against all other good ideas. On their merits. Our role is to let the ideas compete. And ideas that bring the highest value are those which should be funded.

As you and I talk about fund development planning, we are conscious that ideas like a community charitable pharmacy are worth putting forward for funding because they out-compete other ideas by their measure of patient health impact. As leaders, it is our job to discern the best ideas, and to strive to gain funding for those that are most effective for the patient.

Fund development can be a very frustrating topic for nonprofit leaders, particularly when neighborhood-level charities begin dealing with institutions such as hospitals, and for hospital departments attempting to align funding for department focus. That frustration can be overwhelming.

First and foremost, all business agreements happen through relationships. This may be surprising for those of us new to business, who assume that business agreement is first and foremost transactional. The truth is, most seasoned leaders look for a relationship first (meaning trust, respectfulness, honesty, reasonableness, competency, business acumen, agreeableness) and then work out transactions (who gets what and what it costs) later. For those new in the field of fund development, it does not matter how good your idea is or your execution will be if the relationship is not yet in place. Become known as a reasonable, trustworthy, stable, and considerate leader and know that those qualities will bring your funding 75% the way there. Reputation and relational connection is the seedbed for business partnerships.

The sad news is that this irrefutable principle in business may take some time to develop if you are a new factor in a community or in the hospital. Get known and get respected. There is always funding for good ideas and a community charitable pharmacy is an exceptionally good idea. Such a model produces sustained improvement in health among the most complex patient populations, and does so at a fraction of the cost of other healthcare programs. But funding happens through trusted relationships, followed by accountability and follow through.

Consider your hospital as an island and on that island live four different tribes. Each tribe has a different language that they speak. Let’s say that you have a very good idea that will benefit this island, but you need these tribes to collaborate with you. If you do not become fluent in each of the four languages, there is no way that you can persuade the whole island to do what you wish, even if what you wish is best for them. They can’t agree until you answer their questions, and to understand their questions, YOU HAVE TO SPEAK THEIR LANGUAGE.

Think of the following as features of your communication with the hospital, conveyed in meetings, presentations, and your business planning/budget…

- Healthcare Funders speak (but not primarily speak) the “Heart” Language – The Heart Language is actually the least spoken language within the funder’s walls (which may be surprising to hear). It tells how we made the world a better place. While it is true that everyone in healthcare speaks this language (you do not go into hospital administration, healthcare foundation management, or medical school unless you care for people), if you speak only to the heart about how you can or are making the world a better place, then you will confuse and frustrate those asking questions in other languages.While it is important that your effort considers the FACE of those impacted and speak the heart language – patient lives, age, gender, numbers in the community, their stories, what those lives are going through, the responsibility of the hospital for those lives, etc. – It is a big and common mistake for people who serve outside of the healthcare funding arena to approach the funder with funding ideas, conveying the concept mostly with heart messaging.

- Healthcare Funders speak the Financial Language – this is an important language and it tells what it cost, what was the return, and when that return came. It is spoken primarily by the Chief Financial Officer and the Chief Risk Officer, but every foundation and resource-rich environment’s executives speak the financial language. This language is fluent in cost, return, probability of savings, and risk associated with failure. Examples – budget, performance, ROI, and throughput data.

- Healthcare Funders speak the Health Outcomes Language – this language tells us if we improved patient health, where was that improvement, and how we measured that improvement in health outcomes. While this language is primarily spoken by the Chief Medical Officer, Chief Nursing Officer, and Chief Pharmacy Officer, every leader in healthcare funding understands and speaks the health outcomes language. To convey answers in this language, your business plan needs to capture the language. Examples: health impact by disease state, hospital length of stay data, readmissions, etc.

- Healthcare Funders speak the Plumbing Language – this is the language that tells us how we improved the health system flow, impacted efficiency, and lowered risk within the healthcare continuum. The language is spoken by the Chief Operations Officer, and Chief Strategy Officer, but again, every leader who controls healthcare resources speaks this language. Those creating a community charitable pharmacy have an amazing story about routing avoidable hospital discharges and ED encounters through the charitable pharmacy and saving money and resources for the local healthcare community. Leaders who speak this language are always looking for ways to impactthe three-legged stool of healthcare – reduce cost, improve patient experience, and increase health outcomes.

A charitable pharmacy distribution point has one of the most powerful messages in healthcare that can be conveyed through the four languages. If you become fluent in all four, you have one of the most compelling stories to share in your island.

Tip: Storytelling as Best Practice by Andy Goodman is a helpful resource for telling your organization’s story.

There are two types of funding needed to launch a charitable pharmacy: seed funding and ongoing funding. Seed funding addresses the initial planning and startup expenses of a project, whereas ongoing funding covers the post-implementation, day-to-day costs of a community charitable pharmacy. These two types of funding cover different phases of the nonprofit’s organizational life cycle (launching work versus ongoing service delivery work). As such, the needs differ between funding startup and ongoing efforts. Similarly, the character and expectations of seed funders are different than ongoing funders. For reasons outlined below, it would not be uncommon to be declined seed funding by a funder with the profile more akin to supporting regular post-implementation service delivery. This section will attempt to explain the two types of funding, the needs of the funders, and how to approach each on a program’s way to sustainability.

Seed funding is the term that represents the initial dollars needed to cover expenses associated with the launch of a program. As such, seed funding is heavy on the kinds of expenses that would count as new, one-time costs (capital expenses to purchase a facility, renovation costs, personnel firm hiring searches, initial marketing design work, initial legal expenses, etc.). More nonprofit programs fail at conception than at adulthood as the most vulnerable days of a new nonprofit are its early development. A seed funder will shoulder the burden of funding the highest risk period for a program (its earliest days of service) and covering the cost of some of the costliest program expenses. The nature of seed funding must be far more tolerant of program risk and the potential for organizational failure. Therefore, seed funders must be cultivated in a way that acknowledges the higher risk to the funder.

Unknowns create risk. Seed funders wish to make sure that the leaders overseeing the creation of the program are as thorough as possible with a plan to manage unknowns. Planning reduces some of that risk and lowered risk means a higher probability of success at a lower cost. Since the risk profile for a new program is much more tenuous than a program with 10 years of operating experience, funders must be cultivated initially that will be tolerant of the risk.

Seed funders have different questions and different expectations than ongoing funders. A solid business plan is required by most seed funders. For instance, since there will be no program history to provide, program leaders will need to provide benchmarking data and examples of the programs they envision. Replication of proven programs and an actionable plan are desirable for seed funders – who are often eager to confirm that there is a business plan in place for a community charitable pharmacy. A sound business plan demonstrates that the program knows what it will attempt to create, will know how much money is needed over a given time period to create that program, and will know the way that the program will measure success over time (See: The Fund Development Plan and the Fund Development Planning Process).

Seed funding opportunities differ from ongoing funders in type as well. Funders with a higher tolerance for the increased risk of seed funding typically include those with a closer proximity to a program’s work (same community, rather than a federal or national funding concept), and are ones with a more direct potential benefit for the program’s successful work. Prospective funders with a close proximity and a greater potential benefit include:

- Local hospitals – Next to patients served by the community charitable pharmacy, the local hospitals will have the greatest financial and mission benefit from the work.Seed funding conversations should engage hospitals early and should seek to understand issues such as:

- What is each hospital’s perception of the need for increased medication access among the poor? (Is medication access a topic in the hospital’s strategic planning?Has medication access been identified as a strategy for increasing the health of the community?Has medication access registered in the local health department with the Chief Public Health Officer, and/or in the local nonprofit hospital’s community health needs assessments?)

- Is the hospital looking to save money among the self-pay/uninsured population by improving the health of the uninsured through the provision of stable access to a robust formulary of essential medications?(Where is the Chief Medical Officer on the topic of chronic illness management and medication access?Is the hospital’s director of pharmacy amenable to expanding medication access for the poor?)

- Is the hospital in a financial position to partner with the leaders of the community charitable pharmacy in the goal of opening a robust and functioning charitable pharmacy? (Where is the Chief Financial Officer and the Business Development Office on the topic of investing into a community-wide solution to lack of medication access?)

These and other questions can be answered through relationships with the local hospital, partnering and communicating the opportunities to move medication access forward in the community.

- Local Foundation Grant Investment – Foundations are grantmaking organizations that seek to partner with local charities to achieve a defined mission. That mission is a statement that is publicly available for review, listed in each foundation’s annual IRS990PF (an annual tax document available for free to view on Guidestar.org). It is important to approach foundations with a mission that is complementary to the work of your community charity nonprofit.

Most foundations distribute a percentage of an endowment each year. The distribution process is overseen by a board of directors responsible to ensure that the funding distributed aligns with its mission. Being caretakers of an endowment, foundations may be a bit more willing to absorb the risk of funding a startup concept, especially when the business case and replication demonstrate the community charitable pharmacy has a solid plan and a lowered risk. For that reason, a foundation may be willing to contribute to a risky startup venture when other funding sources cannot tolerate the potential risk of a funded failure.

It is always best to follow the process for a funding request outlined by the foundation. However, when not explicitly discouraged by the foundation, it is recommended to request a meeting with a foundation to share about the work that the community charitable pharmacy aims to do and to understand:

- Does the foundation accept funding requests solicited by the community, or are funding offers only extended to organizations approached by the foundation?

- What is the foundation’s level of comfort in funding a new effort?

- What kinds of pre-work planning is typically required of a foundation to support a new initiative?

- Corporations and Corporate Foundation Investment – Corporations may offer funding to the community, either as direct support from the revenue of a corporation or through a charitable foundation tied to a corporation. When considering the opening of a community charitable pharmacy, consider the businesses that are at work in the community, and seek to meet with that business to understand:

- Does the corporation fund community efforts?

- Is the focus of that funding compatible with the work of the community charitable pharmacy?

- What is the corporation’s level of comfort in funding a new effort?

Fund Development planning is the exercise of creating an actionable plan to lead fund development efforts. It is a written vision, activities, due dates, and measures around which your fund development work can take place. The goal of the fund development plan is to:

- identify funding opportunities and resource-rich relationships,

- prioritize those opportunities by likelihood of success, cost, and return; and

- begin each using project management principles.

It is generally suggested to begin the fund development planning process with a meeting of key leaders. The assignment before and during the meeting is to brainstorm funding opportunities. After the opening remarks, introductions, and discussion of the vision of the meeting, start by brainstorming funding opportunities where every leader in attendance shares their ideas for funding the work. After all ideas are recorded on a whiteboard or poster paper, allow the room to define the:

- cost,

- return,

- probability of success, and

- political or influencing factors related to each idea. See: Environmental Factors.

The goal is to compare each idea on their own merits and assign an objective value to each idea. When completed and the cost, return, probability of success, and influencing factors are defined, allow the room to rate each idea against each other to assign a priority. The goal is to identify the top 5 or 6 ideas and ask for volunteers to lead each idea. When completed, create a project management matrix for the top candidates (goal, measure of success, the top 3-7 activities, due dates for each activity, person responsible for each activity). Then begin the work!

For examples see:

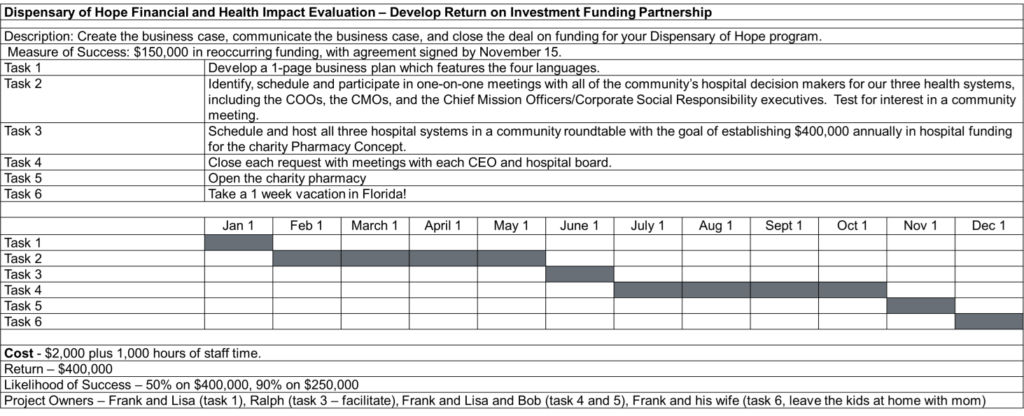

- Figure 1 (below)

- 2018 Sustainability Plan Ozanam

- Fund Development Toolkit

- Fund DevelopmentPlanning and Brainstorm

Figure 1

Finding funding is the starting point for securing investment. A typical mistake for nonprofit charities is to assume that there are national sources for funding a charitable pharmacy. The reality is that the financial, health, and mission benefits of a community charitable pharmacy are close by, rather than distant. Therefore, funding is more often going to be found close by, rather than distant.

The following is a series of resources that you can use to identify potential funders:

National Resources

- Foundation Center Database –This service is a subscription-based database which provides searchable access to every foundation in the United States. Information includes items such as the total endowment of each funder, the annual giving, the members of the board, and the approach process. Further, results can be filtered by foundation location, foundation service area, and types of causes addressed by the foundation. It maintains the most comprehensive database on United States and, increasingly, global grant makers and their grants — a robust, accessible knowledge bank for the sector. It also operates research, education, and training programs designed to advance knowledge of philanthropy at every level. The Foundation Center has 5 regional hubs and over 400 funding information centers across the country. An example of the use of the Foundation Center is to conduct a search of every national foundation that might have a presence in your specific city and which are concerned with healthcare access for low income adults. The results of such a search include details on the list of foundations and contact information for each.

- Guidestar –provides free access to the IRS 990s produced by foundations. An IRS 990 is a United States Internal Revenue Service form that provides the public with financial information about a nonprofit organization. Included on this document are fields mandated by the Internal Revenue Service. They include total endowment, annual expenses, vendors, investment portfolio data, board members, and gifts given. Typically, submissions to GuideStar run two years behind the current date. An example of the use of GuideStar might be a search of all of the IRS Form 990s of all of the organizations that are similar in mission and are located in your community, which would give you a feel for what kinds of funders are investing into the health of the uninsured in your community.

- Grantsmanship Training Center State Resource Database – This resource provides a searchable list of funders in each state. The information is general in nature (top givers, corporate foundations, community foundations) but it does provide a free starting point for funders.

- Grants.gov – This portal provides a central repository for information on federal government grants, as well as tools to support grant applications, grants management, budgeting, and other grant writing activities.

Local, State and National Funding Resources

- Local Hospitals – Hospitals have the most to gain in your success. Community charitable pharmacies have a large impacton the health of the uninsured, and can therefore impact the financial position of the hospital (See: Return on Community Investment (ROCI) Funding and relationships).

- State and Local Government – A smart place to begin your search is to sit with the Mayor’s Office or meet with the Governor’s staffto understand possible funding to open a community charitable pharmacy.

- Individual Donors – Community leaders of considerable financial ability often have a deep concern for healthcare. Identifying such leaders may not be easy, but by asking other leaders in the community, it is possible to meet with those who have the interest and ability to launch a community charitable pharmacy. Funding of this type will require a solid business plan and trustworthy leadership. Like all funding, the relationship comes before the transaction.

- Local Corporate Foundations – Corporations like to be positive neighbors in the community. An approach to the largest corporations in the region is worthwhile, but not until your initiate has researched the past giving of every corporation. Past giving is a good indicator of current interest and willingness. Know that funding should only be requested after a meeting. Again, relationship and trust come before investment.

- Faith Community – Many large denominations have funding programs to serve the low income, vulnerable populations. Speak with area ministers, imams, and rabbis to learn of and access these funding pools.

- Pharmaceutical Manufacturer Foundations – Often among the most generous and largest foundations annually in the US, foundations of the largest manufacturing companies may have funding programs to help support the work of a community charitable pharmacy.

Some funding is based on the generation of new revenue, such as a loan that a bank may give to a grocery store in order to help that grocer begin a business that generates revenue. However, with charity efforts that serve those in need, charity investment is often provided in the hope to avoid expensive and less efficient costs. In other words, ROCI funding is an agreement to invest into a charity that will save avoidable expensive costs on the part of the funders. As an example, ROCI funding may solicit $300,000 in seed funding and $100,000 in ongoing funding per year in order to avoid $500,000 annually per hospital in the local healthcare economy’s three hospitals. The cost is the startup and ongoing staffing of a charitable pharmacy. The return is that 1,000 patients each per hospital will be served with consistent access to medication. The investment goes into opening the pharmacy, with the benefit provided by the community charitable pharmacy back to the hospital.

An ROCI funding relationship asks the following questions…

- What is the cost of the present system?

- What is the cost of the future system?

- What is the delta of those two financial realities?

- Who pays that cost?

- Who will receive the benefit?

- Is there capital enough to invest into the new system?

Some partner’s pain points your community charitable pharmacy could solve for them, and the benefits that the partner would experience include.

Potential ROCI Partner |

Current Cost (Pain Point) |

Potential Return |

Investment Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitals | Avoidable emergency department and inpatient care | Savings in IP and ED care due to consistent access to primary care medication through a charitable pharmacy | Seed and operating dollars to start and maintain the community charitable pharmacy |

| Patients | Lowered health status and quality of life Reduced employability Lost work time Presenteeism |

Supporting the community charitable pharmacy through donations and service fees | Fees, donations, and service charges |

| Doctors | Lost time and personal frustration of prescribing meds that a patient cannot afford | An easy, simple answer for patients to get medications, as well as a prescribing formulary for the uninsured | Seed and operating dollars to start and maintain the community charitable pharmacy |

| Employers | Lowered health status and quality of life for workers Diminished workforce Reduced employability Lost work time Presenteeism |

An easy, simple way for workforce to experience improve health outcomes | Seed and operating dollars to start and maintain the community charitable pharmacy |

| County, State, and Federal Government | Reduced tax income on earnings Lowered quality of life and satisfaction of the population |

A low-cost mechanism to improve the health of the low income, and increase the productivity of the workforce, including increased taxable income | Seed and operating dollars to start and maintain the community charitable pharmacy |

| Local Healthcare Foundations | Frustration in achieving a mission of improved health outcomes among the chronically ill | Measurable impact on health improvement among the uninsured | Seed and operating dollars to start and maintain the community charitable pharmacy |

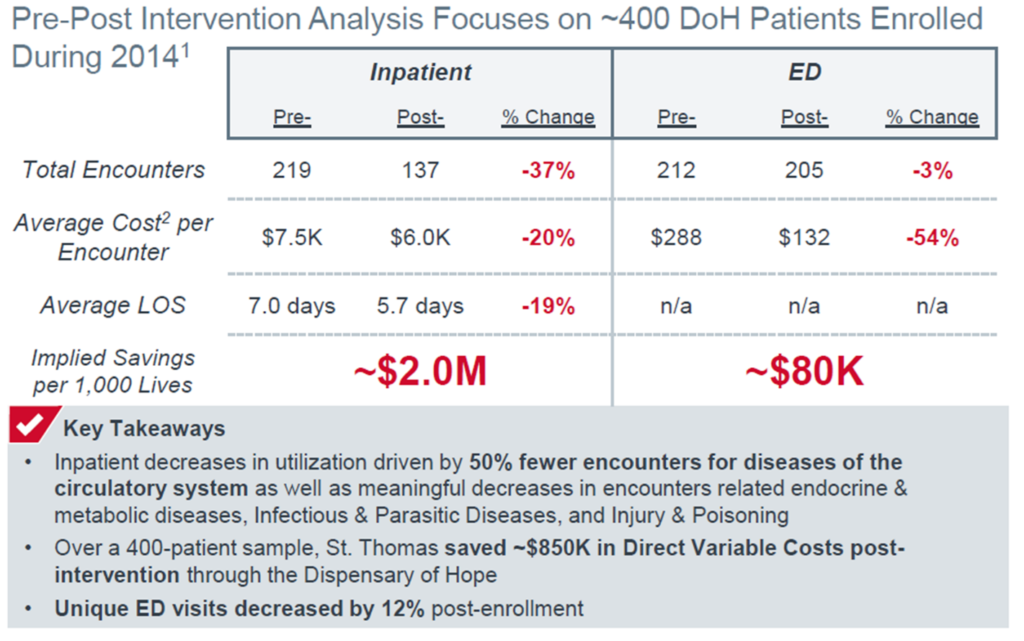

Research shows that community charitable pharmacies are playing a role in a qualitative and cost savings difference for these patients who are served. In 2015, a pre-post analysis was completed by the Advisory Board Company that looked at the work of a charitable pharmacy. That study demonstrates cost avoidance impact related to medication access, specifically on the costs of hospital care for the uninsured.

Total inpatient encounters decreased 37% from 219 to 137 while average length of stay decreased by 19% from 7 to 5.7 days. The overall cost per encounter was reduced 20% from $7,500 to $ 6,000. The average length of stay decreased from 7 to 5.7 days. Total emergency department visit use decreased 3% from 212 to 205 visits with a 54% reduction in cost per encounter from $288 to $132. The implied savings per 1000 patient lives totals $2.1M with $2 million for inpatient visits and $80,000 associated with emergency department visits. The takeaway is that community charitable pharmacies are playing a role in cost savings difference and outcomes difference.

Since this is a population that represents only cost to a hospital (reimbursement is very low among the poor and uninsured, and sometimes not even worth pursuing for financial and for risk reasons), a healthier uninsured population means savings for a hospital and for insurers

Please refer to Fund Development Toolkit Tool #1 where it displays decision tree for Fund Development. The decision tree helps think through the process of getting started with an idea (new service line) and evaluate your funding options and opportunities. Notice that every funding model is going to be different based on specific needs and resources available in the community. For best practice, pursue those opportunities that have the greatest likelihood of success.

- Earned income – Earned income is revenue income from traditional pharmacy services such as prescription, MTM service, and consulting services. Any revenue generated by services served is earned income.

- Subscriptions – Subscriptions are a subset of earned income. This is a program where patients pay monthly subscription fee and enables the pharmacy to provide any medication in which the patient qualifies. This is a rare model for pharmacies because most work with pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) or Medicaid/Medicare insurance. With this new model, pharmacies don’t accept insurance and do not operate under a PBM. The pharmacy develops their own model that is very non-traditional. Nevertheless, subscription program allows your pharmacy to generate steady cash flow and increase the value of your pharmacy.

- Retail – Retail is any revenue generated by filling medications.

- Public & State Funding – Public and state funding are very important areas. It’s now becoming more relevant. An example of public funding is to operate the pharmacy by getting medications donated from other health care system such as long-term care pharmacy. State funding involves working with your state legislator to operate drug donation program. For some pharmacies, the drug donation program generates the highest revenue and is what keeps the organization sustained. Many charitable pharmacies may not get contracts to operate this program but it’s possible through advocacy. Building relationships and communicating the importance of the program to the community with the lawmakers help advocate your cause. Start with the state legislator that is connected to pharmacy or safety net health services; find an advocate for your cause/program and they can go to other members of government and share that story. You can bring in other community leaders such as local hospital CEOs and free clinic administrator as your advocates. When the legislators see the need for charitable pharmacy, it puts pressure on them to try to come up with a way to make it happen. (See: Stakeholders and Funders and How Much Did We Do or How Many?)

- Foundations – Foundations are a type of funding available from other organizations. This allows for your pharmacy to use funding from different areas as a match from other organizations. Visit Foundation Center to search and apply for foundation organizations. For more information go to Fund DevelopmentToolkit Tool #2, to learn how to find and cultivate foundation investment.

- Hospitals – Hospital funding applies to charitable pharmacies that are part of large health systems. The large health system can see the value of providing free or low-cost access to medication to their patients. If their patient is not able to take medication, their condition could exacerbate resulting in a readmission to the hospital. Therefore, hospitals that have charitable pharmacies help reduce hospital costs. In many cases, hospitals have revenue streams that are required to be invested in a charitable pharmacy. Additionally, revenue generated from 340Bprogram are reinvested into the safety net.

- Grants– Grants are typically funded by foundations. The challenge is finding a grant that is a good fit for the charitable pharmacy. A great way to find funding is through the federal grants website www.grants.gov. Refer to Fund Development Toolkit Tool #4 and Grants and Funders to find websites and resources for grant funding. In many instances, it’s not about finding a grant that already exists, but you can present the idea to an organization and they can turn around and present your pharmacy a grant to invest in the program. When presenting your idea to potential investors, make sure to include the return on investment advantage that shows the financial impact of the work. Please refer to Fund Development Toolkit Tool #5 for more information. Obtaining grants also depends on advocacy and building relationships within your community. As an example, the Iowa Safety Net Pharmacy noticed a need for a mental health program for inmates in their community. Many inmates do not have access to medical care and their medications upon leaving jail, thus their conditions deteriorate and may result in further incarceration. Iowa Safety Net Pharmacy reached out to their local government official to present the idea which landed them a grant to start the program. They now offer a corrections program that provides immediate primary care services and up to 90 days of behavioral health prescription drug coverage for transitioning offenders released from the county jail (See: Incarceration).

- Fees/Waivers – A waiver is a type of voucher program. Different pharmacies operate waivers differently. For instance, the Iowa Safety Net Pharmacyprovides uninsured patients with a voucher for the patient can then take it to a pharmacy and have a prescription filled. The pharmacy submits the voucher and get reimbursed for the medication they gave.

- Contract work – Contract work is another opportunity to work with the community to help replicate similar programs. For instance, these could include offering consulting services. Contract work is utilizing the expertise from the leaders that are part of the charitable pharmacy.

- Partnerships– Forming partnerships is one of the most critical avenues of funding and advocacy. Partnership is a way of creating relationships with other like-minded organization such as the local health system, or community health clinic to provide services (See: Top 10 Ways to Grow Your Charitable pharmacy Volume). This can be a contract service. For instance, there is a Dispensary of Hope pharmacy in Iowa that was contracted by their local pharmacy association to dispose of drugs and they get paid for the service (See: Final Incineration).

- Technical School – This is a type of funding that utilizes workforce training initiatives. Knowing that there is tremendous shortage of certified pharmacy technicians, and tuition being expensive for employees, some charitable pharmacies create their own pharmacy technician program to generate revenue. Your charitable pharmacy can develop a platform where a pharmacy technician certification program can be provided via online resources in combination with experiential hours in the pharmacy.

- In-Kind – In-kind is a type of donation that does not involve cash grant. The donations provided are contribution of goods or servicesother than monetary exchange. For instance, hospitals could offer lease free space or donate certain hours of work to the pharmacy. Volunteer work is also considered an In-Kind donation (See: Students and Volunteers).

Get access to the full playbook

Get instant access to the full playbook, with more than 150 pages of valuable guidance, case studies and resources to help you develop your charitable pharmacy.