Metrics, evaluation and outcomes are essential to measuring and sharing your successes and opportunities and demonstrating what is actually being done. They are useful to:

- Attract funding – If your idea is successful as determined by evaluating metrics, it will attract potential funders who want to support good ideas.

- Spread the vision – Great outcomes from established programs encourage new programs to start and existing programs to improve and expand.

- Deepen integration locally – Sharing outcomes with free clinics, Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), hospitals, departments of health and others help them understand the impact of your work.

- Credibility – Your credibility establishes trustworthiness for the charitable pharmacy and the services

Success depends not only on the right “product”: improved medication access to the uninsured and improving health outcomes. Being truly successful in achieving a charitable pharmacy mission includes ensuring a proper “supply chain”: staff adequately trained in pharmacy skills and for the particular population being served. Equally important is a relationship of trust and education:

- Patients understand how and when to use medication, common adverse effects, and access to and provision of other resources that promote health and stability (food, housing, social services, etc.)

- Providers who act as referral sources to your pharmacy and are collaborators with the services they provide

- Community government, hospitals, clinics, churches, and all who can collaborate with your charitable pharmacy to build a healthier community

Gathering qualitative and quantitative data as you go establishes standards and allows for adapting processes frequently. Staffing can be shifted to areas of most demand. Services with the most impact, such as disease or service-specific education (CHF, diabetes, MTM, device utilization, smoking cessation), may be expanded. Other services that have less impact or are a service that can be offered from another resource, for example, types of PAPs, may be reduced or eliminated. Evaluation allows for funding to funnel to what has the greatest impact and encourages gains in funding for practices that show a positive impact. Measures of variability provide opportunities to train best practices across the supply chain.

- Do you have an internal process for testing ideas? How will you know you are successful?

- Do you have strong relationships with your patients and regularly ask them for feedback on servicesoffered and impact on their health and economic wellbeing?

- Do you solicit patients input when introducing new processes or teaching techniques?

- Have you developed a list of all stakeholders who can influence your work, directly or indirectly?

- Do you provide spaces in staffmeetings, reports and/or fund meetings to have open conversations about failure?

- Do you have a mechanism to incorporate lessons learned from failure?

- Do you regularly assess programmatic priorities to ensure focusing on areas of greatest impact?

- Do you have a process to discontinue programs or activities when they are not having an expected impact?

Adapted from Social Startup Success

TIP: Funders may offer training to grantees on measures and models of measuring. Example: Fairfield County Community Foundation offers their grantees seminars on Results Based Accountability, the tool they use to measure organization impact.

After collecting data, measuring, and evaluating your charitable pharmacy and validating the impact it is having on patients and the community, communicate these results both internally – with staff and board members through meetings and dashboards- and externally – to supporters, funders, stakeholders via newsletter, webinar, input call, or presentation. Consider presenting your model or findings to professional organizations (local, state, national) to help other charity and ambulatory care pharmacies to better serve the uninsured. (See: Share Results below).

The Dispensary of Hope has a set of metrics that it asks partners to share which includes the number of 30-day fills, the number of unique patients, and the total number of patient encounters. Health system outcomes may be measured as a percentage decrease in 30-day hospital readmissions which can be very difficult to measure from an outpatient pharmacy standpoint. These outcomes can be measured readily at neighboring hospitals that share patients with charitable pharmacies. To show continued measures of success, some useful metrics that can evaluate program utility include: emergency department utilization for preventable visits related to lack of primary care and potentially preventable disease complications, inpatient visits, length of stay, and cost savings associated with the reduction of these visits.

Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness or return on investment (ROI) of the Dispensary of Hope program at your pharmacy can be calculated by measuring the number of doses dispensed through the program and the cost savings of a subscription to the service. A 2015 study conducted by the Advisory Board Company on a study hospital in Nashville, TN showed an average cost savings of $645K for a large hospital or an ROI of $3:1. (See: ROCI and Dispensary of Hope Advisory Board White Paper.)

Results-Based Accountability (RBA) is a model used to organize the metrics you collect and demonstrate their impact. RBA is used by state governments, grant funders, and others as an accountability tool for their programs. Measures can be used to improve programs and make them more effective. Another metric tool is Theory of Change), which helps demonstrate causal links between program activities (providing medication access, MTM services, etc.) and the organization vision (fewer ED visits and hospitalizations, increased primary care visits and improved community health.) “It’s about following the flow of activity to the ultimate impact. The activity itself is not enough to measure; it’s the impact of that activity which makes the metric so meaningful.” Natalie Bridgeman Fields, Accountability Counsel, Social Startup Success, pg. 63)

The three kinds of performance measures are “How much did we do?”, “How well did we do it?”, and “Is anyone better off?” Most of the measures you collect fall into one of these categories.

How Much Did We Do or How Many?

- Patients – new, returning, demographics

- Prescriptions(Rxs)– new, refills, synchronized refills

- PAPs – total PAPs submitted, approved

- Interactions/interventions

- Glucometers/spacers dispensed

- Dollar value dispensed as prescriptions, PAPs, Safety Net

Example: How Many: Dashboard of metrics regarding patients, prescriptions and dollar value for prescriptions

| How Many | Number of Patients Served |

| Patients with prescription filled | |

| Patients with PAPs dispensed | |

| Total patients served | |

| Number of New Patients | |

| New Pts NOT eligible for Assistance | |

| Prescriptions | |

| Number of RX filled | |

| Average # Prescriptions/day | |

| Number of PAPs submitted | |

| Value of Meds(Based on WAC) | |

| HDGB Meds | |

| Dispensed as PAP | |

| Total Meds Value Dispensed |

HOPE Dispensary of Greater Bridgeport (HDGB)

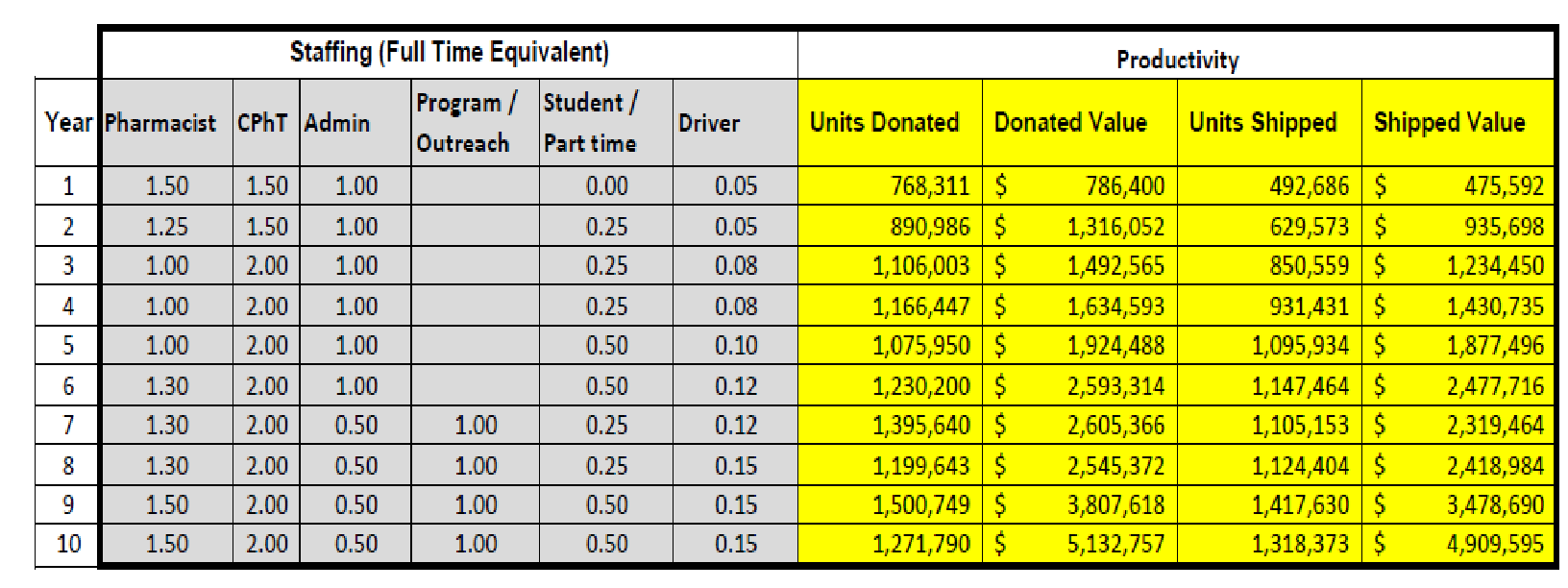

Dashboard from Wyoming Medication Donation Program measuring the number of units (tablets) dispensed and the medication dollar value for 2016. The pharmacy is operational 30 hours per week. Staffing includes 1 full time pharmacist, 1 fill-in pharmacist as needed, and 3 pharmacy technicians.

How Well

How Well Did We Do It? (% of common measures or activity-specific measures). A “How Well” measure evaluates the degree to which a goal/population has been met. When possible compare data from your charitable pharmacy to a reference – from literature, hospital or clinic data, patients with Medicaid or insurance other insurance.

Goals established for measurement need SMART indicators:

Specific: clearly defined

Measurable: objective measurement- “How Many”, “How Much”

Attainable/Achievable: goal is realistic

Relevant: there is a connection between the activity and the intended outcome

Time-Bound: there is a realistic timeframe to achieve the goal

Did we serve patients:

- From all the area clinics

- Within the zip codes covered by our service area

- Within the income levels established

- Not eligible for other types of assistance

- Using multi-lingual services for patients needing them

- Did we meet goals or best practices:

- Average % of patient prescriptions filled on initial visit

- Increase patient compliance as measured by refill rate

- Counseling impact on compliance of a complicated regimen

- Did we need: (workload measures)

- overtime

- extra staff

- changes in software

TIP: Measuring impact is a critical focus of an organization. The presentation of data helps to tell a great story well.

Example: How Well:

Dashboard of metrics regarding referral sources served and patients meeting income (FPL) requirements

| How Well | Referral Sources to HDGB |

| Bridgeport Hosp/Clinic | |

| Optimus Care | |

| Private Practice | |

| SVMC Hosp/Clinic | |

| Southwest Community Health | |

| Other | |

| Federal Poverty Level (FPL) | |

| FPL < 100% | |

| FPL 100-199% | |

| FPL 200%+ |

HOPE Dispensary of Greater Bridgeport (HDGB)

Tracking referral sources helps measure the effectiveness of marketing and partnerships with other stakeholders or partner safety-net organizations in our community. It also allows monitoring if re-education needs to occur to a particular referral site (internal or external).

Map of density of uninsured patients in area served with number of patients served and prescriptions filled by Zip Code. (See: Geo-mapping in Local Factors for Community Charitable Pharmacy Implementation and Appendices\Marketing\Building a Map of Impact.docx).

Is Anyone Better Off? or Benefit/Impact

Is Anyone Better Off? (skills, knowledge, attitude, behavior, circumstances) “Better Off” measures demonstrate the benefit or impact of services on the patient or the institution/community. Impact measurements may include intermediate outcomes or goals that lead to achieving the final vision of the charitable pharmacy. An intermediate goal could be improved or stable number of patient primary care visits and the vision or success goal is to decrease ED visits and hospitalizations.

Patients

- Measurable clinical outcomes if available (A1C, blood pressure, lipids, etc.)

- Regular use of maintenance meds in comparison to rescue meds (inhalers)

- Proper use of devices

- Interventions

- Renewed applications (patient-perceived benefit of program)

- Patient dollars saved by coupons, vouchers, therapeutic interchanges

- A patient satisfaction survey can be a tool to measure patient’s perceived impact of pharmacy services on their health, economic, or other areas of their life

Institutions or Community

- Cost avoidance

- Potential billable amounts

- Referrals

- ED visits, hospitalizations, primary care visits

Example: Better Off:

Dashboard of metrics regarding measures of benefit to patients and the community

| Better Off | Patient Impact |

| Interventions and referrals | |

| Collaborative Practice | |

| Therapeutic Interchanges | |

| Community Impact | |

| Cost Avoidance | |

| Potential Billable Amount | |

| Volunteer/Education Hours |

HOPE Dispensary of Greater Bridgeport (HDGB)

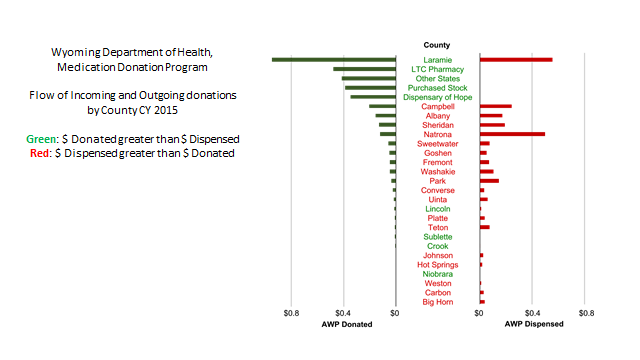

Wyoming Medication Donation Program (WMDP) relies heavily on county donated medication as their source for dispensing. The formulary is supplemented by reclamation of meds from Long Term Care facilities and pharmacies (LTC), purchasing meds, and non-profit vendors. The following chart is used to encourage counties to donate medication samples and quantifies the value of medication dispensed to patients within the counties.

In RAB terms:

- How Many dollars of donated medications (value) by Wyoming counties versus amount spent to acquire meds from vendors and reclamation

- How Well is the WMDPserving the state of Wyoming and its counties based on the value of medication dispensed and number of counties being served

- How Well is each county contributing donated medication samplesto WMDP

- Better Off: by county, dollar value of patients benefiting through medication access

WMDP reports a Return on Investment (ROI) to communities consistently above 5 (value of Rx’s dispensed (AWP)/program cost). In 2015 the value was $10.77. See Return on Community Investment (ROCI) Funding.

Performance metrics for drug donation and reclamation programs will vary greatly depending on:

- Donation source (long-term care, health system, or individuals)

- Types of medications accepted (prescription only, over the counter, or disease-specific, durable medical supplies)

- Program model (centralized repository, logistics only, dispensing or wholesale)

- Staff structure (professional staff, volunteer-based, or mixed)

The following metrics were gathered from a state drug donation program in Iowa that utilizes a centralized repository for the state, collects medications from long-term care facilities, clinics, pharmacies and individuals, and distributes medications to participating pharmacies and clinics utilizing a wholesale distribution pharmacy license. The table shows the volume (one tablet = one unit) and the value of incoming medications that were donated, inspected and accepted into the program, the volume and value of medications that were distributed to participating clinics and pharmacies, and the professional staff utilized each year to achieve the results.

Drug donation programs are complex operations. The operating procedures, program design, staffing structure, and services offered may require significant adjustment in the initial years of operation. The program will become more efficient over time as various components of the program are evaluated and refined every year.

These measures are used internally and externally to shareholders to demonstrate growth, efficiency, and value of outreach (footprint).

TIP: Be creative with indicators of progress. SIRUM measures not only how many pounds of medication they redistribute but also the reduction of medication waste they prevent.

The key to data collection is keeping it as simple as possible.

| Data collection that fits with normal workflow | • Satisfaction survey

• Limit time frame • Utilize technology if possible |

| Utilize residents, students and volunteers | • Students: pharmacy, healthcare, foreign language, business, pastoral care

• Volunteers: retirees, service hours for professional programs |

| Adapt techniques from literature | • Trial what has worked in literature into present setting

• Provides comparison when presenting data |

Many pharmacy software products are adaptable and/or vendors will work with you to create reports to demonstrate your metrics. (See Pharmacy Management Systems; Dispensary of Hope Software Webinar; Resources.) Software products are also available to manage and track volunteers.

Implementation of performance metrics to assess pharmacists’ activities in ambulatory care clinics presents measurable pharmacist functions that impact patient outcomes and mechanisms used to document these services.

TIP: Is there something you do exceptionally well or is unusual? Find a way to measure it and promote your excellence.

Example: student volunteers conducted a patient survey but also helped hugely with filing. The volume of files was correlated to a case of paper to show 500 pounds of charts managed.

Example of software (RxAssist Plus) method for collecting clinical intervention data with assigned dollar value:

| Intervention | Potential CMS Billable Value | Estimated Cost Avoidance |

| Add Medication | $20 | $92.95 |

| Adverse Drug Event | $20 | $276.12 |

| Allergy Detect/Clarification | $20 | $187.37 |

| Drug Information or Therapeutic Consult | $20 | $47.89 |

| Discontinue Med | $20 | $80.24 |

| Dosage Form Change | $20 | $63.88 |

| Dose Change | $20 | $82.25 |

| Med Reconciliation/ Transition of Care | $20 | $30.12 |

| Medication Change | $20 | $40.88 |

| Patient Education | $10 | $35.21 |

(Values referenced from Outcomes MTM and Implementation of performance metrics to assess pharmacists’ activities in ambulatory care clinics)

Schools of pharmacy and other programs, such as business management and statistics, are a great resource for evaluating outcomes. The schools need to conduct research and publish, providing a win-win scenario for the charitable pharmacy and a school of pharmacy to partner.

Outside Experts may be recruited or found at Volunteer Match and Taproot Foundation

A satisfaction survey is usually subjective but demonstrates the patient perspective which can influence compliance and perhaps other outcomes.

- Questions can reflect objective data, e.g. over previous 6-12 months number of visits to primary care provider, visits to emergency department, hospitalizations.

- Subjective questions demonstrate patient satisfaction with services provided, perceived health, economic or other benefits to using the charitable pharmacy, and can act as an education point to reveal options to services offered. See examples in satisfaction survey and Implementation of performance metrics to assess pharmacists’ activities in ambulatory care clinics

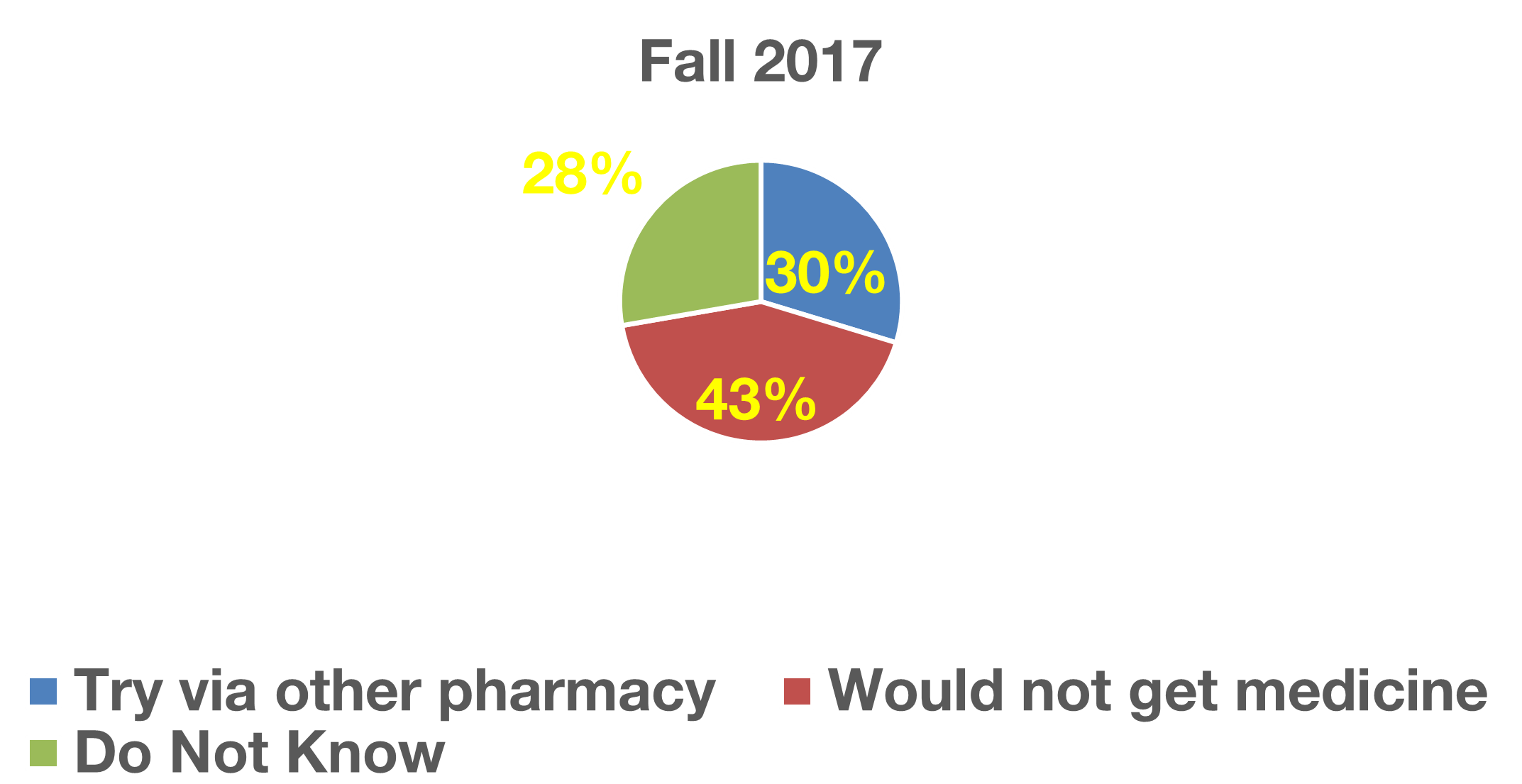

Example of Survey Results Conducted by Fairfield University Students for HOPE Dispensary of Greater Bridgeport

World map of those countries represented by HOPE population

Students don’t always realize there are poor in the United States or that immigrants come from across the globe.

“Before this class and our time at HOPE, I did not know about the population in the US that does not have health insurance or access to health services.”

How would you get your medicine if you did not have access to HOPE?

Results from a patient survey: 43% of patients interviewed would not get their medicine and another 30% did not know what they would do.

Determine focus of study: What will the study address? How is this different from previous research, in the literature or your organization?

Establish concrete goal(s) for the study: What is trying to be accomplished? (not the outcome, but what will be measured.)

Three factors for a successful research project include recruiting and sustaining a qualified research workgroup, addressing financial needs, and developing a solid research plan.

Develop a research workgroup based on:

- What is the goal of the research?

- What systems/organizations/providers are impacted by this project? Include prescribers, departments of health, hospitals and/or clinics, healthcare providers, academia, community organizations, other pharmacies, transportation providers, community leaders, board members, etc.

- Workgroup should include members familiar with the subject being addressed, including front-line workers, administrators, providers, volunteers, students and any others involved with the processes.

- Have an executive sponsor or principal investigator who takes responsibility for the study.

Inclusion in research workgroup

- Contribution of skills needed to complete the study. Interest in goal, statistics, administrative, professional

- Review curricula vitae, resumes and biographies of potential interested members

- Availability and willingness to dedicate time for conducting research. Develop an approximate ask time for specific tasks for study – hours/week, number of weeks. Will time be voluntary or paid, available as regular or additional staffing hours?

Responsibilities of workgroup members

- Establishing study design and goals; consider use of Stages of Change Model

- Identify benefits and risks to participants and community

- Investigate need of Investigational Review Board (IRB) (usually through hospital or academic institution) See Determining if IRB approval is needed

Develop a research team

This is the team who will be conducting the research and the ongoing analysis. Key will be determining those within the organization (volunteers, staff, students) with the appropriate skills and abilities to conduct and/or support the study. See Inclusion in research workgroup

Training those conducting research:

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) including signed agreement with organization(s) involved

- National Institute of Health (NIH) Protection of Human Subjects Education Note: tutorials are no longer updated as of September 2018, but site includes informatics defining Human Subject Research and tutorial prior to September 2018 with quiz.

- If you think your study does NOT constitute research involving human subjects, consult Comparison: Characteristics of Human Subject Research Versus Other Project Types

- Develop training materials that include clear procedures and processes (as in Standard Operating Procedures) to ensure consistency of tasks by all team members. Competency with performing tasks should be measured.

- A checklist verifying training and competency is beneficial for analysis, liability and stakeholders. Materials should be signed and dated by both researcher and trainee to be kept with research materials.

Develop a Research Plan

- This is a business plan for the project

- Create a budget based on direct (e.g. office and medical supplies) and indirect costs (space, utilities, technology, staff compensation).

- Other factors besides financial include legal, Investigational Review Board (IRB) processes, facility or designated space requirements, and time limits and expenditures.

Steps for Research Project

Not required to be completed in sequential order, but all items should be completed prior to implementation of project.

- Define focus and goal of project. Can your research provide evidence to change practice within the scope of practice (Evidence-Based)? Is there a pattern of evidence emerging from the organization’s practice that may not be described in current literature? Is there a gap in current literature that this research may fill?

- Develop a research statement based on the question the study will address. Statement should be specific, not be too general, too vague, or too ambitious. Example: Impact of pharmacist-led Medication Therapy Management in collaboration with healthcare providers on patient-reported health outcomes.

- Review relevant literature. Does project meet a gap? Are there methodologies that could be used for this project?

- Develop study design: randomized or non-randomized; control or no-control; double-blinded.

- Develop subject participation criteria (age, disease state, length or severity of illness, literacy, income, language, other).

- Establish ethics of research. Participants should not be coerced to participate. Consent is obtained. Written or verbal information is in the language and literacy level appropriate to participants. Risks are minimized and there is a potential for benefits (risk-benefit ratio). HIPAA permission is obtained, stored and compliance is maintained.

- Determine methods and data to be collected From this, design policies and procedures for the research team.

- Construct a research proposal based on Research Plan. This is used for community and organization support, collaboration and funding.

- Receive IRB approval if needed.

Project Implementation

- Those conducting research are trained in their roles, methodologies, data to be collected, etc. Methods should be clear, repeatable and consistent by all researchers.

- Data should be collected clearly and accurately, utilizing technology whenever possible.

- As well as clinical data, monitor: subject recruitment process, time commitments, follow-up, and dropout rate.

- Pilot study may be used evaluate processes, collection of data relevant to project, time commitment, and quality and quantity of data

- Team meets frequently to evaluate processes See Improving Care Delivery through Lean for a model of implementation.

- Utilize Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) to refine processes, such as setting upper limits of participants/team members, reasons for non-participation or return for follow-up, etc. Review study documentation for accuracy, streamlining, and compliance with local health officials, external sponsors, ethics committees or academic institutions.

- Research Workgroup oversees project.

Analysis and Interpretation

- As much as possible, determine data points prior to beginning study or as soon as points become apparent to ensure necessary quantity and quality of data.

- Minimum of 50 study participants are required to achieve statistical significance

- Clear and accurate interpretation of data can be done by a statistician or using medical statistics software.

- Analysis is a time-consuming process; allow time for this.

General |

Optional |

Pharmacy specific |

Billing |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Sharing results that establish social justice requires a two-pronged approach. First, to establish meeting the social need: as a charitable pharmacy improves medication access for the uninsured. The second is education to others, including stakeholders and funders but also the next generation, professional colleagues, and the community.

Who might want to see the results?

- Stakeholders: sponsors, funders, community, healthcare providers, patients (See: Stakeholders and Funders for use of sharing your results with stakeholders).

- Methods such as dashboard, PowerPoint, or newsletter work well to share results with internal stakeholders or external stakeholders who are familiar with the work.

- Professional Organizations: local, state, national, CharityPharmacy.org

- For professional education, use of an oral presentation, PowerPoint, webinar, poster, or published article is recommended.

The pharmacy professional organizations, American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists (ASHP) and American Pharmacists Association (APhA), offer guidelines to create a professional poster presentation. If you consider a formal research project, clinical research involving patients requires approval by an institutional review board (IRB) and, if appropriate, informed consent from patients. Example abstracts are provided.

For example, HOPE Dispensary offers some sample topics that do not require IRB review:

- Establishing and evaluating a charitable pharmacy collaborative practice agreement

- An overview of charitable pharmacy for urgent care and emergency department physicians

- Evaluation of verbal counseling, written directions, and a visual aid to affect adherence in a culturally and linguistically diverse urban population

- Implementation of a Medication Therapy Managementintervention in ambulatory care settings: experiences and lessons learned

- Transitions of care

- Utilization of therapeutic interchange to improve access to medication in a low-income uninsured population demonstrating patient dollar savings

Get access to the full playbook

Get instant access to the full playbook, with more than 150 pages of valuable guidance, case studies and resources to help you develop your charitable pharmacy.